The starting point for this research was the astrolabe. An ancient instrument used by Islamic astronomers from around 550 AD, the astrolabe was made up of elaborate sliding metal discs and pointers, which were aligned to celestial bodies in order to give answers to astronomical, astrological and religious questions. Later on, this early measuring device had its moment in European history. It proved invaluable in helping to propagate and teach Islamic geometry during The Renaissance, and then, during the European age of empires, it was instrumental in maritime “discovery” expeditions.

Recognizing the astrolabe as a network technology that connected humans to a larger network of agents (stars), its function was that of a translator for some of the important questions of its time: harvest dates, prayer times, tidal cycles. The human, the astrolabe and the stars had to come up with answers by performing a ritual together. There was a sense of humility (at least in scale) in recognising that the human was only a part of this system.

In some ways the astrolabe foreshadowed today’s reality of smart objects and networked devices, combining the body, technology and environment, while being intricately intertwined with political systems and loci of power. Having the astrolabe as a reference and a symbol, my interest is in exploring the complex networked relationships between humans, nonhumans and machines.

Thinking about our current systems of communication and infrastructure in terms of Karen Barad’s notion of intra-action (or Timothy Morton’s hyperobjects), we can see that “technology” is not just about technology anymore. In order not to be left out of these systems of knowledge and discourse that we create, we need to resensitise ourselves to these meshes of planetary reach and affect.

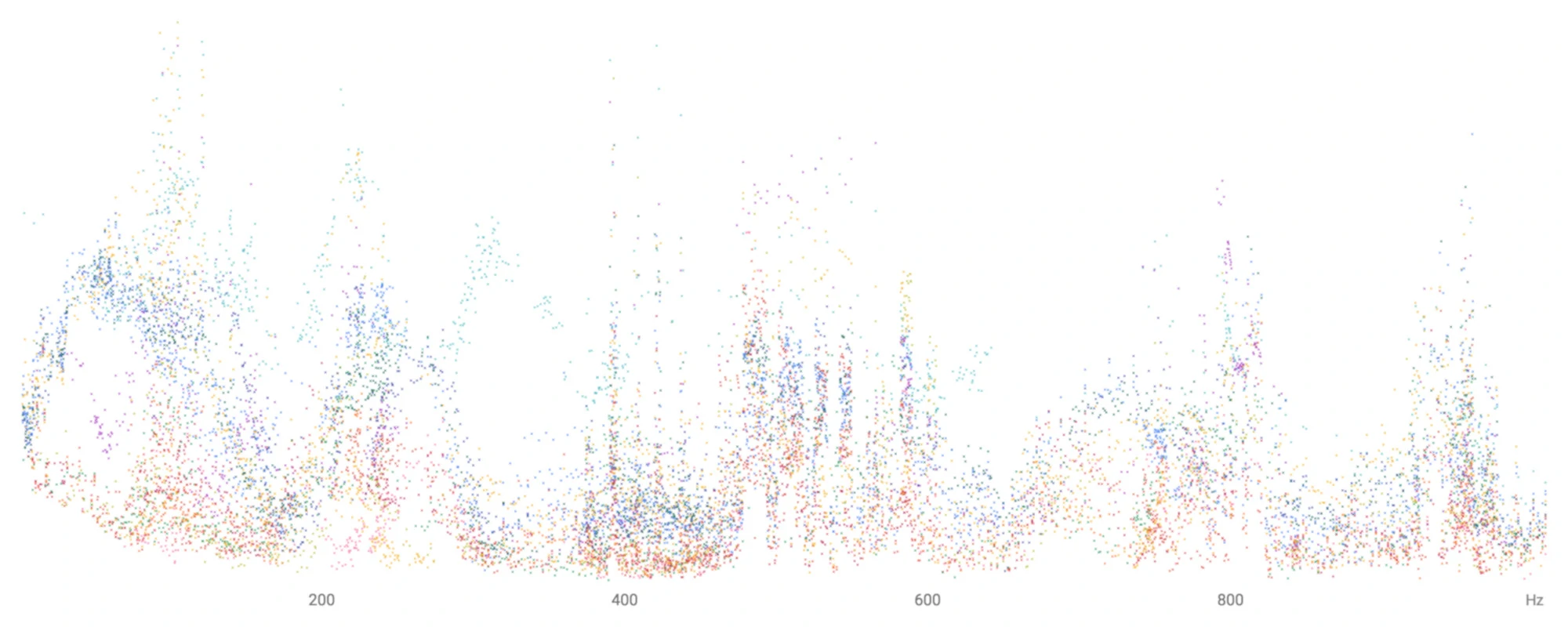

We’ve filled the air with enough electromagnetic waves that it’s not inconceivable to think that these transmission patterns could be read like stars by other machines. Their existence initially dictated by human politics and objective desires, can now be reinterpreted as a kind of dynamic poetry of nonhuman communication, written by never ending cycles.

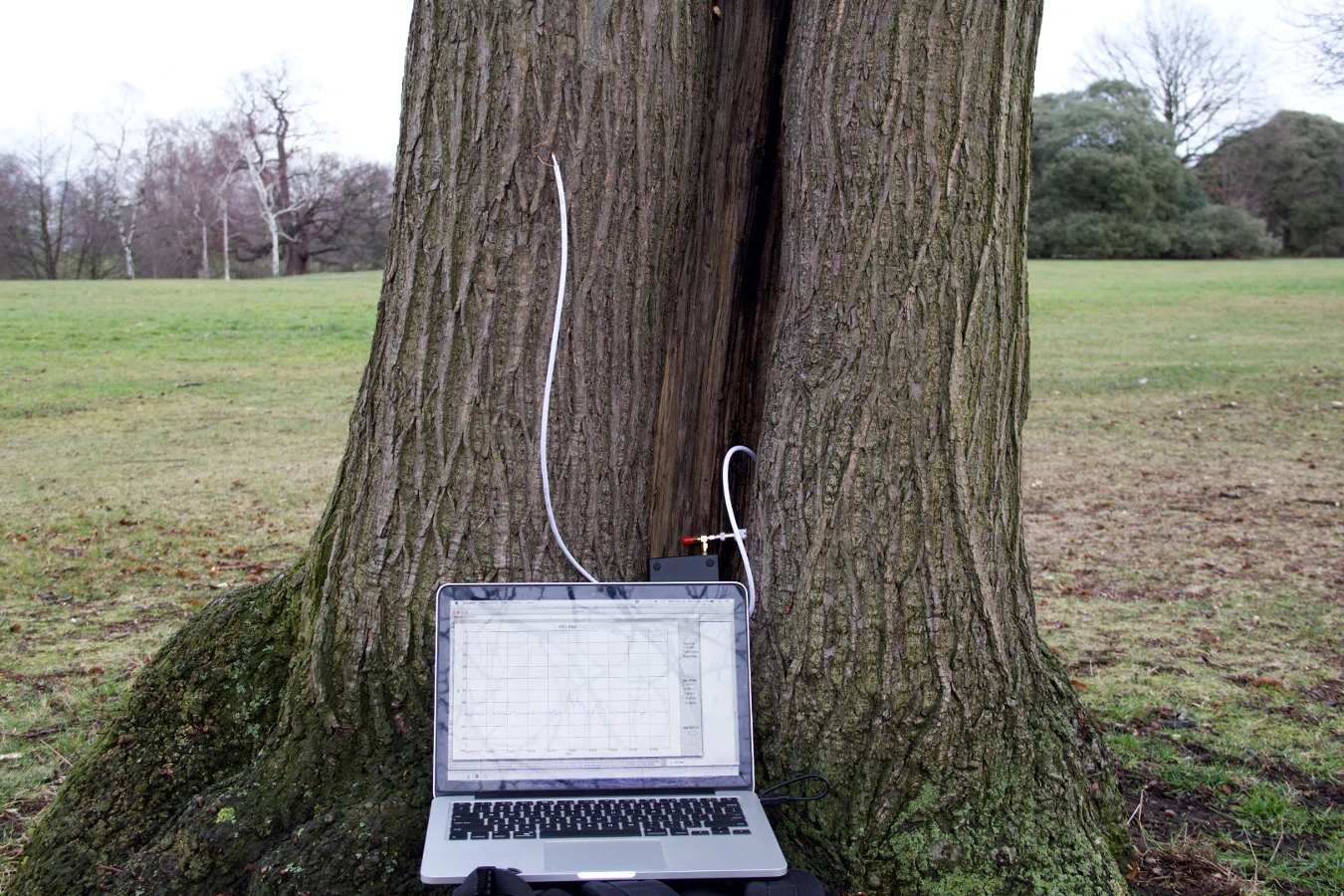

Materially speaking, this research is about the sensitisation of objects and bodies; and the discovery of their sensitivity and reverberations to specific ranges of signals coming from their expanded environment. Poetically, this research explores the possibility of language for revealing the desires, memories and inner conversations of objects and non-human phenomena. It’s an attempt to reach some kind of understanding about how they sense and shape their world, and, in turn, interact with ours.

Given the complex relationships that humans have today with both “natural” systems (as exemplified by global warming, oil extraction, etc), and engineered systems (internet as surveillance, container shipping routes), it feels imperative to avoid the anthropocentric error of always measuring these articulations against the arbitrariness of human linguistic signs and meanings. As Bruno Latour would say, we can’t keep pretending to be modern, holding on to ideals of pure histories, sciences, politics and technology, while at the same time creating these hybrid “monsters” (or cyborgs). Shouldn’t we at least consider alternative modes of representation and communication where the divisions between human and non-human agents and natural and political bodies become less clear?

These are the lines of inquiry of this research: exploring and making explicit the complexities of these relationships (for now in the plane of electromagnetic communications), and creating ways to make these interactions between humans, nature, culture, objects and networks a little more significantly felt.

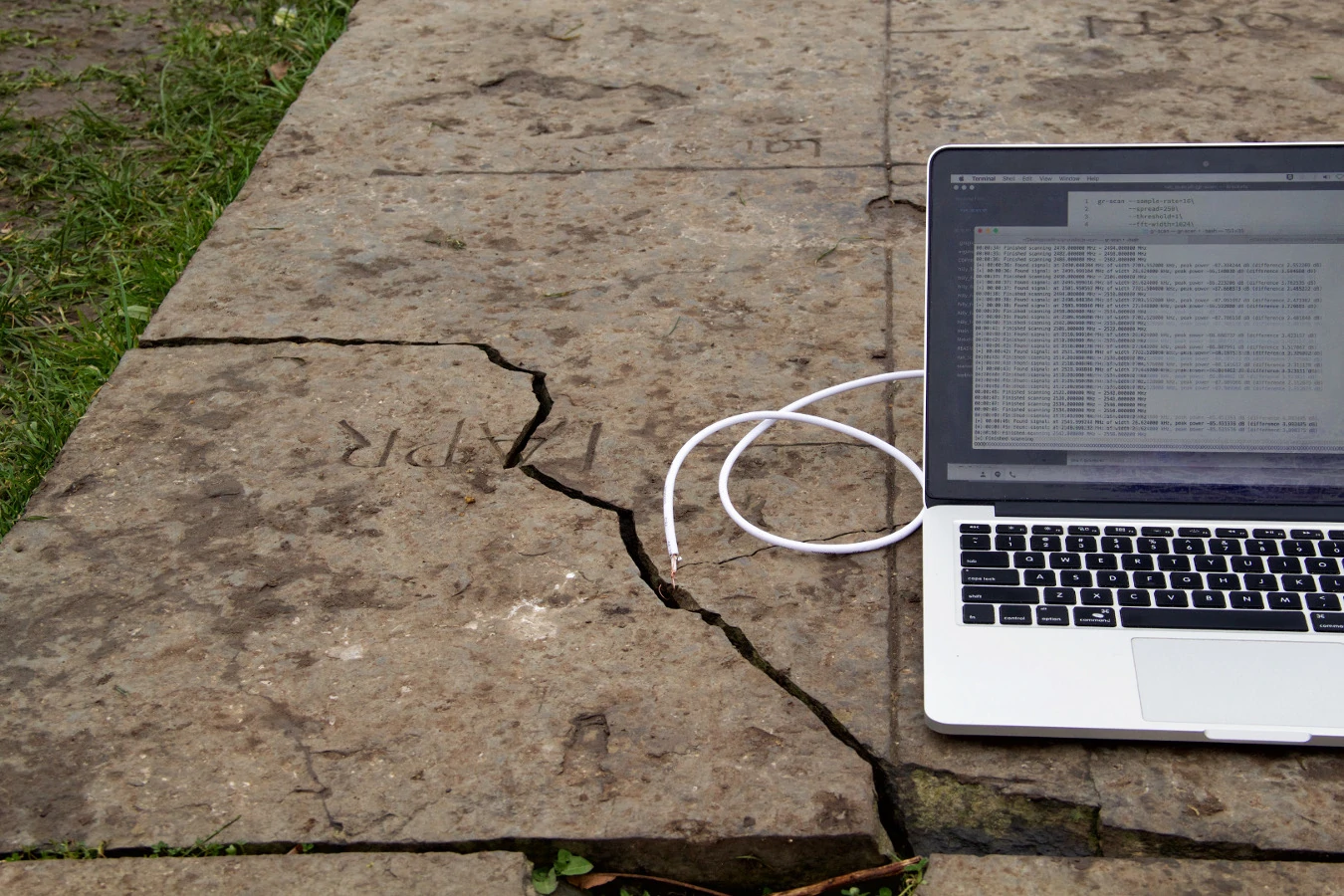

Traditionally, antennae shapes and sizes are chosen in order to amplify specific wavelengths of electromagnetic signals and specific forms of transmissions (omni-directional vs. directional). If we think about this relationship between shape and wavelength from the point of view of already constituted antennae bodies, we can determine the frequencies and types of signals that resonate for objects of different shapes and sizes. Even though they are not consciously felt, we can determine which signals each body receives and amplifies, ignores and interferes.

This project was done in a residency at Delfina Foundation in January and February 2019.

Many thanks to Moonjung Hwang and Genietta Varsi Lari for their help in documenting this research.

[1] Barad, Karen (2003). Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Signs, 28(3), 801–831.

[2] Butler, Judith (2011). Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge.

[3] Calvino, Italo (1997). Invisible Cities. Random House.

[4] Chabot, Pascal (2013). The Philosophy of Simondon. Bloomsbury Academic.

[5] Descola, Philippe (2013). The Ecology of Others. Paradigm Press.

[6] Harawy, Donna (1991). Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge.

[7] Hartigan Jr., John (2014). Aesop’s Anthropology: A Multispecies Approach. U of Minnesota Press.

[8] Latour, Bruno (2012). We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press.

[9] Preciado, Beatriz (2015). Manifesto Contrassexual. N-1 Edições.

[10] Sahlins, Marshall (2008). The Western Illusion of Human Nature. Paradigm Press.

[11] Scheerbart, Paul (2011). The Perpetual Motion Machine: The Story of an Invention. Wakefield Press.

[12] Simondon, Gilbert (2017). On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Univocal.

[13] Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo (2017). A inconstância da alma selvagem. Ubu Editora.