Text from Cidade Queer, a Reader by Júlia Ayerbe.

To all appearances, queer is a term that came to Brazil by plane, landing in the academic world, in symposia, anthropology, and the visual arts. But as a foreign word, what does it enunciate? It is worth recalling that, even before finding the meaning of words, Brazil traditionally and easily swallows them through their signifiers – we are extremely “adjustable” to the sounds coming from the outside.

In the case of queer, it was no different. Originating in the English language, its signifier and signified went through changes over time, and became not only an international concept, nowadays part of the LGBTQIA acronym, but also a qualifier of the cultural industry (as in the TV show “Queer Eye for the Straight Guy”). If in an English-speaking country I designate someone as queer, it is within the limits of clarity. Yet, what would queer designate in Brazil? Is there something unknown that will now be pointed as queer? Would it then be possible to translate it? Barbarize it? Classify it under a norm? How can one do so without normalizing it?

Within the universe of such questionings, and knowing that the Cidade Queer program would result in a book, the Laboratório Gráfico Queer/Desviante came to life. Its purpose was to collectively investigate the possibilities of signifier and signified, formalities, lexical creations, as well as problematizing the visual representation surrounding queer.

LGQ/D

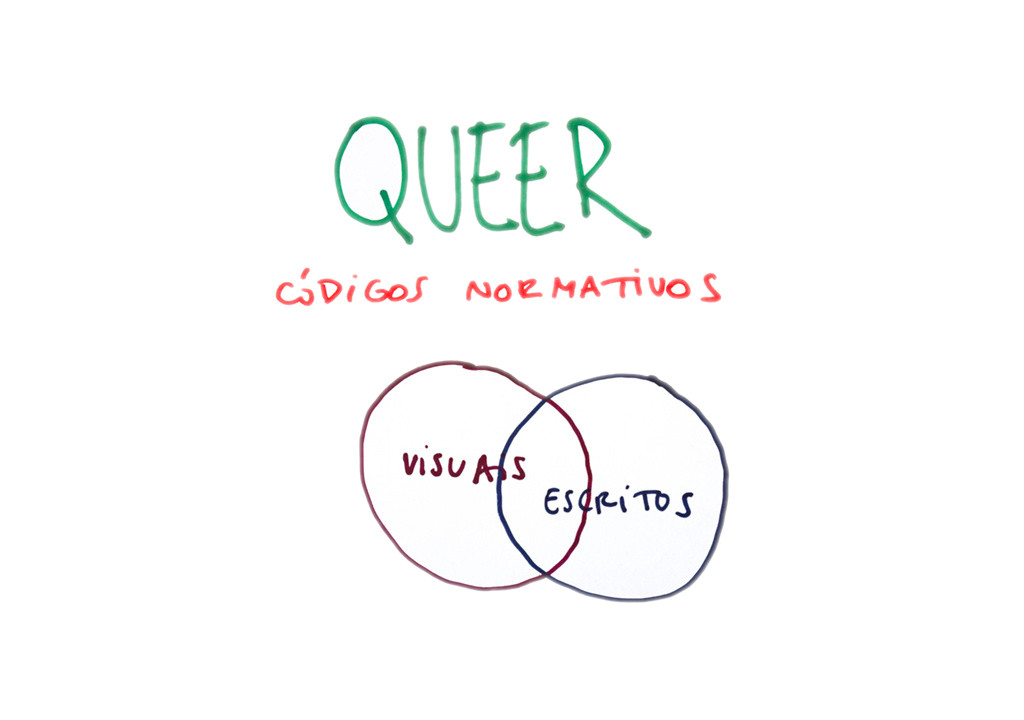

The Laboratory had four meetings, of nearly three hours each, to discuss and study problems around queer and denormatization in both visual and written language. The lab’s most important principle is not to establish new paradigms, i.e., not to think that a problem is solved with the creation of a new structure, for the latter will be as normative as the previous one.

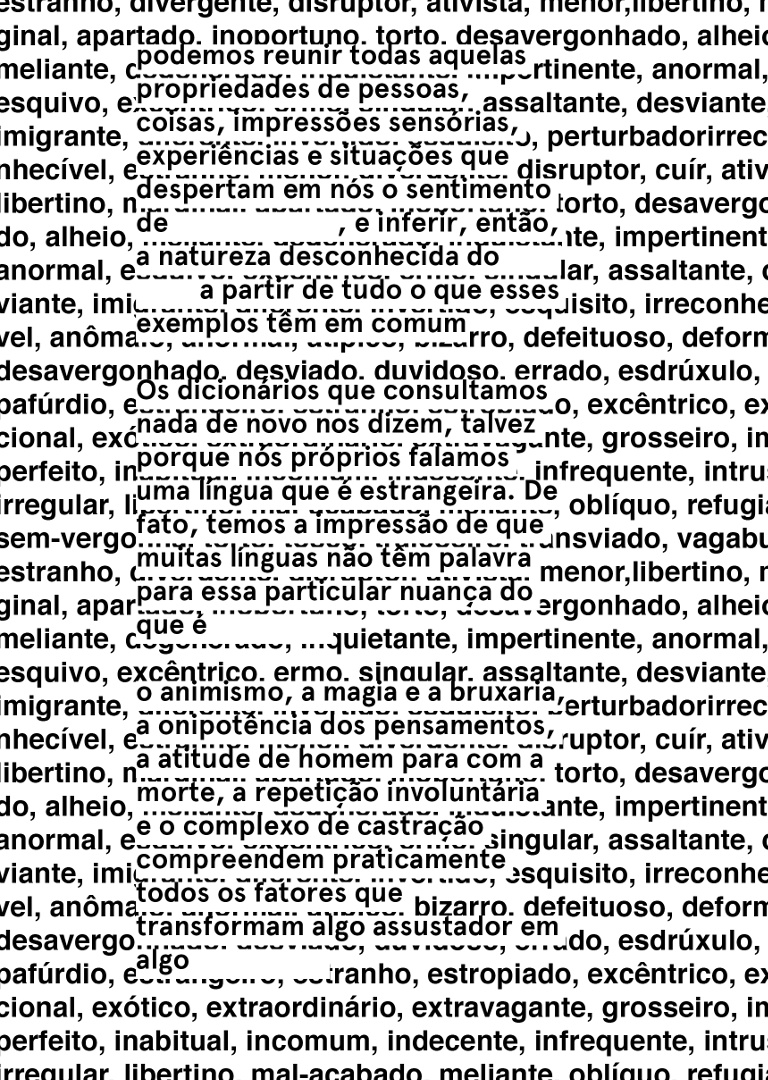

The first axis to be discussed was the translation possibilities concerning “queer”. As from the definition of the Oxford dictionary, we went back to the history of Brazil, looking for neighboring words that could be analogous to the idea of queer. The goal was to create a lexical universe around the concept rather than actually translate it.

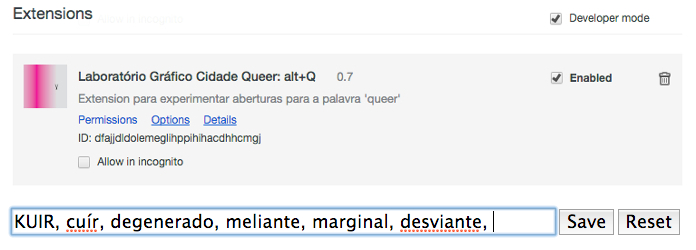

Assimilating that this lexicon, as well as its writing – queer, cuir, kuir – swiftly changes, we developed a chrome extension that alters the word “queer” when it shows up online in a browser, showing its neighboring terms at each page refresh.

The matter of gender markers in Portuguese – and Latin languages as a whole – also presented itself, whether in the predominance of the use of masculine terms for plural constructions or its presence permeating all things (names), at first as an insurmountable issue.

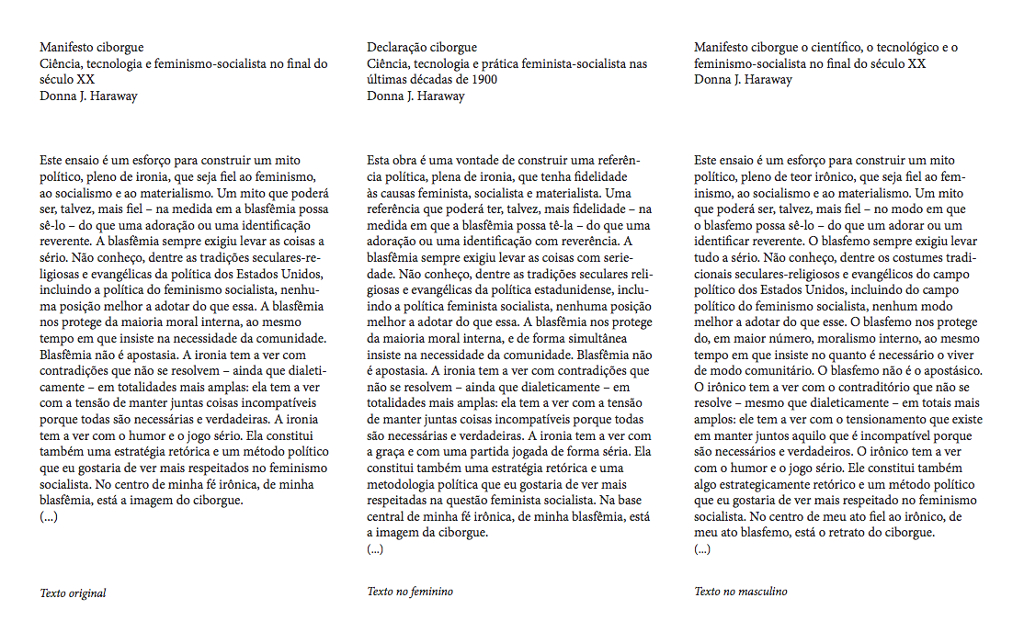

Experimenting with this problem, artist Fabio Morais rewrote the Portuguese translation of Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto in two different versions: one using masculine words, and the other with feminine terms exclusively.

The matter of boundaries between what is said and how it is said raised an important discussion: is it possible to make a feminist publication having a patriarchal language as its grounds? In Portuguese, when we say “we are all feminists”, is this “all” masculine (todos) or feminine (todas)? Is the need for speech greater than the subversion of forms? What is the good measure between these two things?

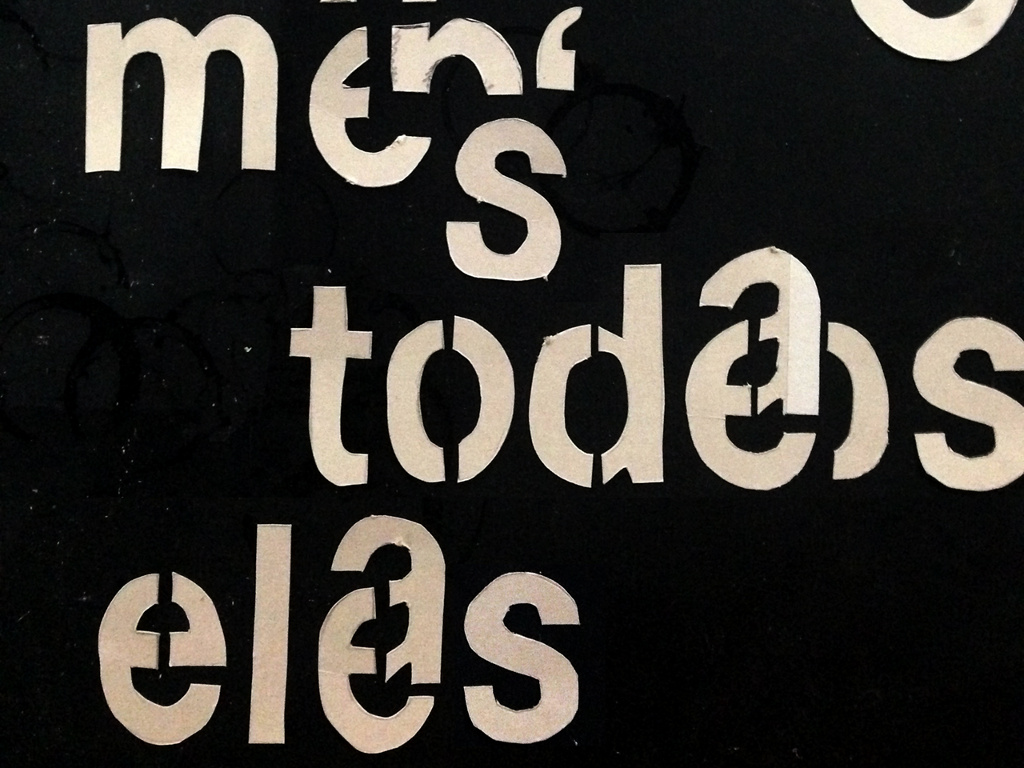

Still part of the same confrontation, we discussed the limits of using “x” and “@” as a solution to replace gender designations with an encompassing of all gender identities, also approaching how it would be possible, in the stiffness of our alphabet and lexicon, to subvert this issue.

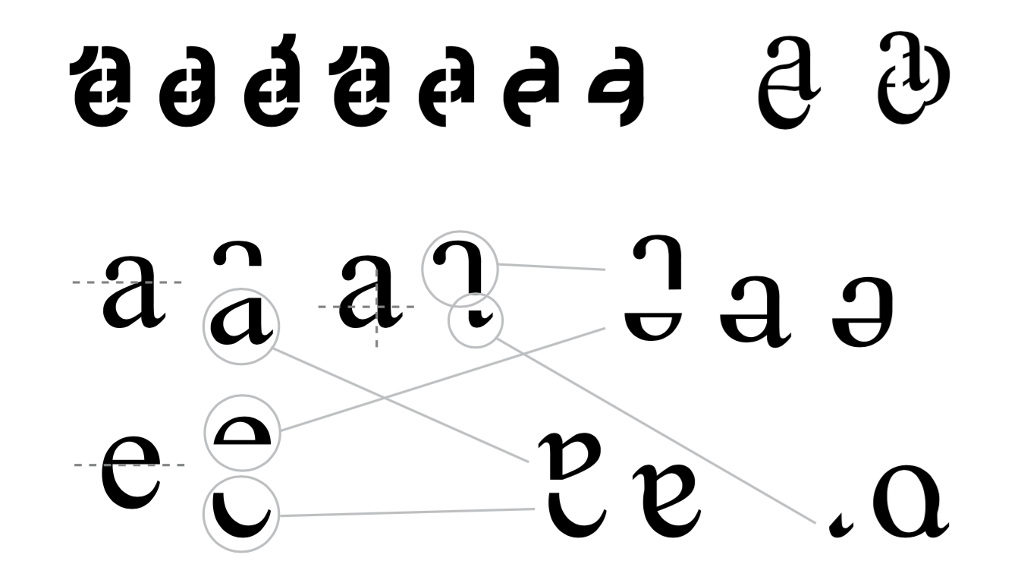

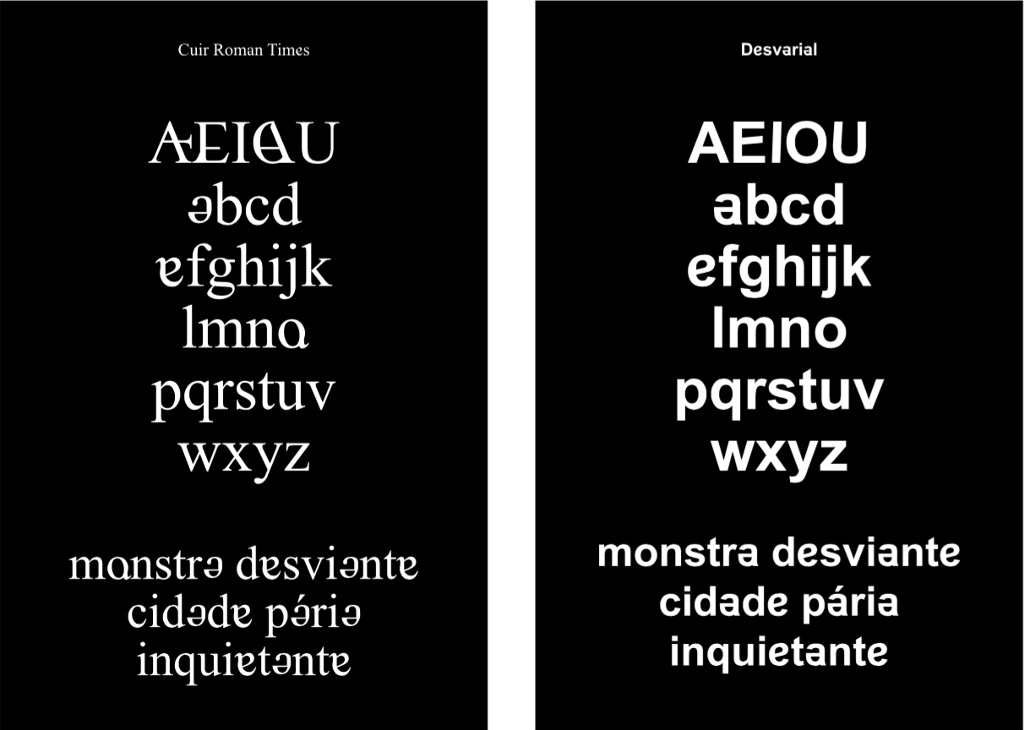

This way, we began to question what a queer vowel would be like, coalescing “a”, “e”, and “o” to allow for an open indication of gender, but without affecting reading (unlike what happens with the usage of “x” and “@”, that somewhat brakes and discontinues the text). Form is intrinsic to content, for we always have to choose a typeface, which brings along a history as well (who are the typographers behind the fonts we use the most, what are their histories?), even if opting for a said “neutrality”.

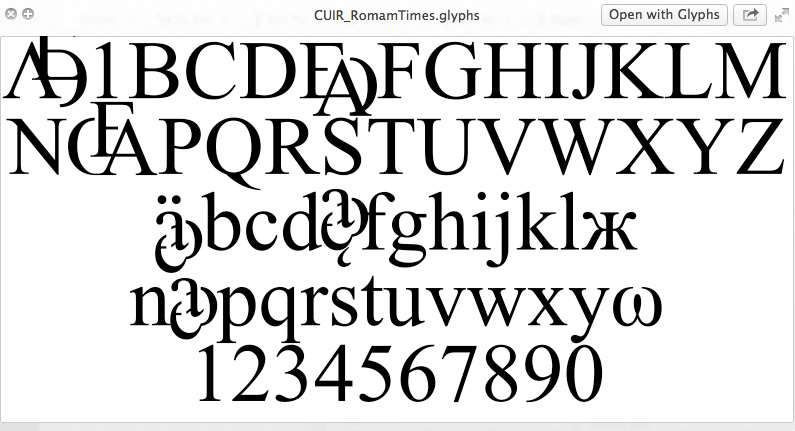

We questioned what a formal vocabulary regarding queer would be like, as well as which cases and colors were associated with it. Since the proposition did not involve the creation of a new normativity, we opted for subverting the most popular and massified fonts – Times New Roman and Arial – instead of developing a new typographic family.

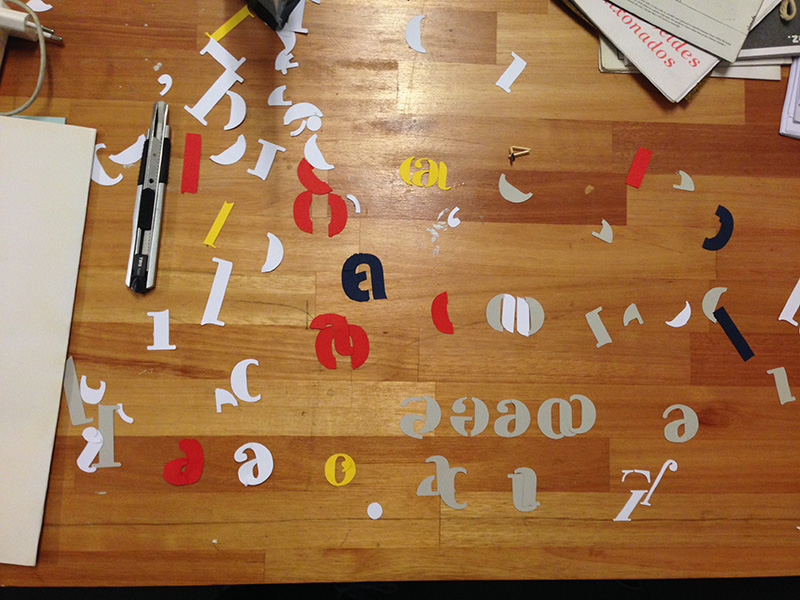

The queer vowel was created from experiments with parts of characters taken from stencils. Since this process is made by previously cutting the font’s glyphs, it resulted in fragments of letters that were then manipulated in order to compose different combinations.

Considering that the idea was to create a typeface to be used in the textual experiments undertaken in the laboratory, we proceeded to interfere in the characters using the font’s digital files. The vowels’ glyphs were vectorized and cut out following the same logic of the stencil, and then assembled in distinct ways. The variation that resulted in the Cuir Roman Times font family, have the glyphs of “a” and “e” fragmented, and their parts inverted and reorganized to form the degenerate vowels.

In an essay from 1919, Freud writes about Das Unheimliche (the Uncanny). The text has not yet been published in Portuguese, but the word is often translated as weird, disturbing – a concept that refers to something that is not exactly mysterious, but rather oddly familiar, arousing anguish, disturbance, strangeness, or even terror. The Uncanny seemed pertinent to us as a reaction of the normative world towards queer.

We then proposed an exercise of mixing Freud’s sentences, leaving a blank space where Das Unheimliche woud have appeared, with the lexicon of related words in the backdrop.

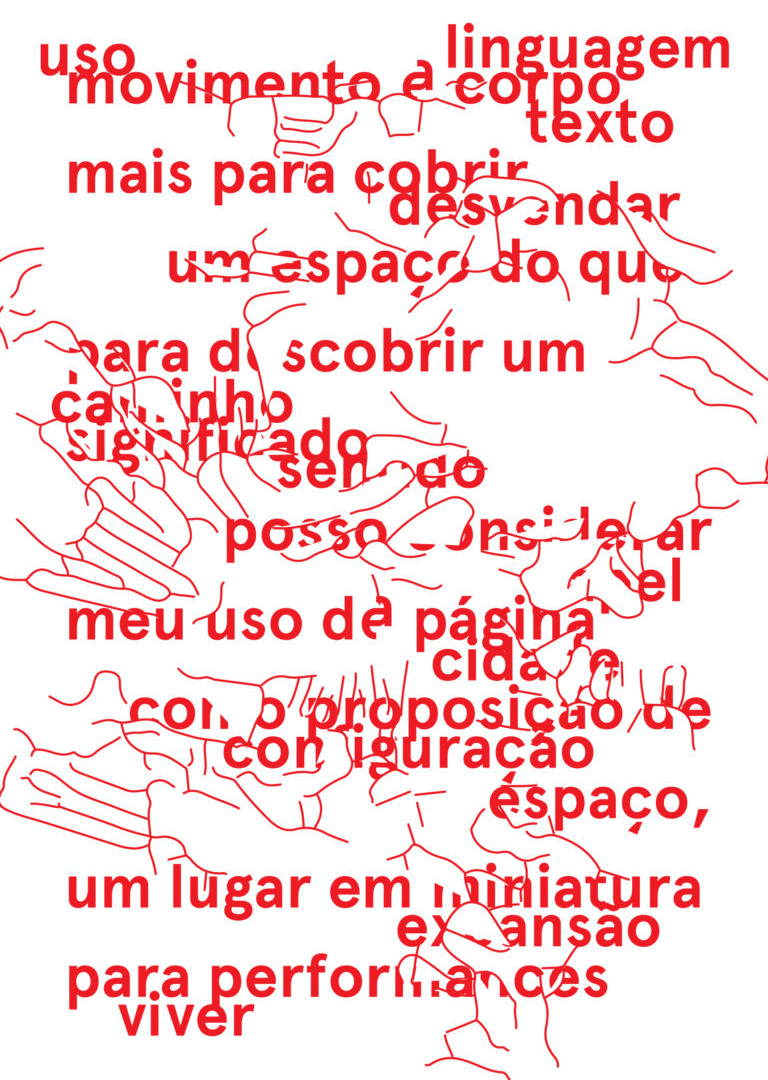

Another exercise involved interfering in sentences written by artist Vito Acconci, in which he approaches the performativity of writing and the city, overlapping them with a sinuous grid taken from the city of São Paulo.

Besides typography, expography and architecture also play a normativizing role in how we read dynamic spaces like a city, an office building or a museum. In 2017, the lab hosted a series of talks and discussions with designers, architects, curators and urban planners to discuss these specific layers that we use to mediate and navigate physical spaces. We studied Ernst Neufert’s Architects’ Data as an example of how normative design/architecture as a language is created and propagated.